Collins Dictionary has an uncharacteristically conversational definition of “day of reckoning”: If someone talks about the day of reckoning, they mean a day or time in the future when people will be forced to deal with an unpleasant situation which they have avoided until now.

Every day this month has felt like a day of reckoning.

Personally, my most painful, cringeworthy, and destabilizing reckoning has been the one that looks at my own internalized white supremacy. How parasitic it is, how I’ve fed it, defended it, kept it alive and thriving, and how oblivious I’ve been to the abusive nature of our relationship. That about sums it up, but here’s an excerpt from a journal entry for those interested in a bit more colour:

“Conforming to the rules of whiteness (particularly my beliefs around ‘this is how one should speak and behave and what is considered ‘proper’) has actually distanced me from my own people and the places that I come from: Tamil culture, Scarborough, the ways my Tamil peers spoke and congregated in high school, my family. I’ve judged them through the lens of whiteness and essentially reconciled myself as separate from them…I’ve talked about my own community, people, culture, and family in an unfavourable light. I’ve judged them. I’ve been frustrated with them. I’ve alienated them. And as much as I hate to say it, I think I’ve thought I was better than them because I was better at conforming to the rules of whiteness…That I’ve been participating in and feeding a system that has never truly served me, at the cost of devaluing / diminishing / deprioritizing and distancing myself from the people, places, and culture I come from.”

—

This personal reckoning is also happening in tandem with the recognition that I work in a system that teaches and preaches English, a colonizer’s language.

In almost every storytelling workshop that I’ve facilitated in the last few months, when asked “What is the biggest challenge you’ve faced in your settlement journey?” the answer is unanimously some version of “Learning the language.” In the past, I wouldn’t have thought twice about this response. Of course, learning a new language is difficult. Over the last little while, however, I found myself waiting for them to say more.

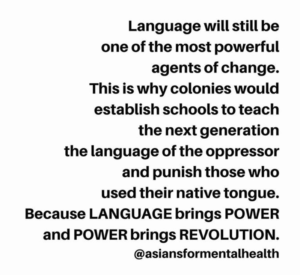

The drinking-from-a-fire-hose experience that had been my last few weeks consuming educational content on Instagram had put me onto several posts that seared the politics of language into my body in a way that I could no longer ignore or minimize. I share these with you below, followed by excerpts of what newcomers have shared with me about learning English, to give you a more holistic picture of how their responses speak to something much bigger and deeper than their individual experiences.

(Image Source: @asiansformentalhealth)

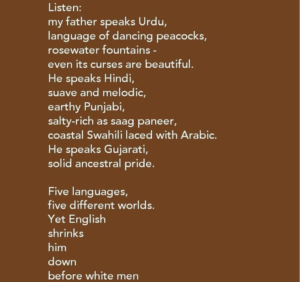

(Image Source: @asiansformentalhealth)

Poem: Migritude by Shailja Patel, Image Source: @brownhistory)

Poem: Migritude by Shailja Patel, Image Source: @brownhistory)

“If I were to give advice to a future newcomer, I would tell them to really learn the English language. Without it, you can’t do anything. You need to be able to speak English to get a job, to make friends, to be someone here.”

“My problem is learning the language. Even though we can all understand each other in the English Conversation Circle, when I’m out or when I go to the supermarket, sometimes I can’t understand native English speakers. It makes me very upset and frustrated. When I go outside, there’s always someone that comes up to talk to me and I can’t understand them. I say, “I’m sorry, could you repeat that again?” I feel so nervous and I try to end the conversation…I always have a headache after. For example, yesterday I was practicing my writing to take the IELTS and I had a strong headache because there was too much information and vocabulary and rules and grammar. I felt like my brain was not retaining information any more.”

“When I learned English in Egypt, I didn’t listen. I just studied with my teacher, but I didn’t listen to Canadian people or people who speak English as their first language. When I came to Canada, I couldn’t understand what people were saying. So I would tell people to practice listening by watching a lot of English movies and listening to Canadian people speak English.”

“All of my husband’s family are all Canadians and every week before COVID19, we always had Sunday dinner together. They all speak English and they make jokes and I don’t always understand them. It’s still a bit difficult…I miss speaking my own language.”

I think it’s easy to chalk these experiences up to the general struggles of learning a language, and tell newcomers to keep trying because “think about how long it takes babies to learn how to speak coherently and they never stop trying.” In reality, there are layers here that are intentionally designed to remain invisible. First of all, comparing newcomers to babies is paternalistic and completely disregards the veiled erasure of newcomers’ home languages and cultures. Secondly, “successful” English language acquisition in Canada is contingent upon buying into the ideology that English is superior in many ways to other languages and that therefore, English should be dominant over other languages. Re-read the last sentence, this time replacing the word “English” with “whiteness” and the word “language” with “race” and there you have it: a window into the larger systems in which the current approach to English language acquisition is rooted.

English, like whiteness, is regarded as the price of admission, and if you can’t pay up, the assumption is that you haven’t worked hard enough, not that the price is unfair or too high. As is reflected in these quotes, one’s sense of worth, access to opportunities, and sense of belonging is directly linked to their ability to not only speak English, but to speak as native English speakers do.

For a country that prides itself on multiculturalism, a country that is happy to inherit the culinary and artistic aspects of immigrant cultures, language acquisition seems to be an exception. For a country that preaches tolerance, the speed and intensity with which newcomers self-police their English – apologizing profusely when they mispronounce something or when someone doesn’t understand them, prefacing questions with “this may be a dumb question”, and chastising their own or each other’s accents – says otherwise.

“For me, my accent is very weird. It’s not like native English speakers. I don’t know how I can speak English fluently without any accent. I want to change my accent but it’s really difficult for me. Maybe it is because the languages are so different. Chinese is an oriental language and English is a Western language. They are totally different.”

“It’s very difficult to create an English-speaking environment in my family. My daughter is an introvert. When she meets strangers, she feels shy and can’t speak with them. I always encourage her to make friends with the local kids who speak English. I want to change her personality. I talked to her teacher and her teacher said that it takes time.”

What’s worse (yes, it does get worse) is that we’ve also set up barriers to learning English. Believe it or not, there are hoops that newcomers have to jump through to drink the kool-aid we want them to drink. For one, we currently discriminate on who can get access to free English classes based on their immigration status.

“I wanted to learn English, but it’s very expensive. If I have PR [Permanent Residency], then it’s not expensive. If I don’t learn English, I cannot find a job. I am waiting to get PR. I want the government to give us any help to learn English that is not expensive. The waiting time to apply to become a PR is really long and meeting the requirements to become a PR is very complicated. It’s a long process. During that time I want to improve my English, but there are no free programs available unless you find a program like [program name omitted to preserve participant’s anonymity]. I also have a little boy and having a child-minding service available would provide extra support along with an affordable childcare program. My husband and I both have professional backgrounds, but it’s a long process.”

White Supremacy Culture (Jones and Okun, 2001) also shows up in the programs and services that teach newcomers English. Earlier this year, a small group of ESL teachers signed up to participate in a workshop we hosted around how they might integrate The Stories of Us resources in their classrooms. One of the teachers, white-presenting, when describing the capacity of their lower level students, quoted them as, “Me no speaky English.” The room momentarily went silent, in a way that we all knew that what was said was not okay, and yet no one chose to name it. We, individually and collectively, prioritized her right to comfort (a characteristic of white supremacy culture) over standing up for the dignity of the students she was (however well-intentionally) describing.

We have also had several ESL teachers – both white and racialized – respond critically to the fact that The Stories of Us books have the English text displayed side-by-side with the author’s home language. Our intention behind this design choice was to honour and preserve the author’s home language, as well as make the story (and the sense of community and connection) it could provide accessible for newcomers who weren’t yet able to read the English text. These teachers however were quite convinced that “If you give them the option of their mother tongue, how will they ever learn English??” Their conviction shook us momentarily as well – we questioned whether we were indeed taking away from the language learning experience we claimed to be enhancing – before we were able to see the paternalism and either/or thinking for what it was. It was yet another manifestation of white supremacy and white comfort in the settlement sector.

The sense of urgency that newcomers feel around learning English is also a manifestation of white supremacy culture. We have created a system in which English language acquisition is tied to employment, credit history, housing, social connections, and immigration status (which is linked to access to essential services like healthcare). That same system also preaches that learning English takes time, that newcomers shouldn’t be so hard on themselves, and that it’s important to take care of one’s mental health. This kind of systemic gaslighting is the equivalent of pinching a baby and rocking the cradle to try and pacify the crying baby (a rough translation of the Tamil proverb, “Pillaiya killi vittu, thottila aatradhu”).

Last and possibly most heart-breaking, learning English as a way of assimilating into Canadian culture and internalizing it as the superior language can also cause generational gulfs within immigrant communities, severing the connection that comes with being able to communicate in the language one grew up with. Jagmeet Singh details his experience with this in his memoir, Love and Courage:

“But forgetting Panjabi meant I lost a little bit of myself and my ability to connect to my roots. It also meant I lost an important connection to my parents. My parents speak English fluently, but you can connect with someone on a completely different level when you speak in the language in which they feel more comfortable expressing themselves. There aren’t any guidebooks on how to build a new life in a brand-new country in a language you’ve only ever studied in school. These were just the learning pains my family came to accept.”

“I wish I had learned Panjabi as a kid and that I had taken my mom’s Panjabi lessons more seriously. I truly believe you can never fully connect with someone unless you speak the language they grew up speaking, the language they dream in. If you love someone’s language, truly love it, then you’ll find a door to their culture, identity, and what makes them who they are. Recently, in 2014, when I was hanging out with my parents and cracking jokes in Panjabi with them, what I’d been missing as a kid hit home. Not speaking my parents’ language had left a gulf between them and me. When I finally spoke our mother tongue with my parents, I felt a new bond form between us.”

—

With that, I will sign off today by acknowledging again: I work in a system that teaches and preaches English, a colonizer’s language.

Clearly, as the length of this blogpost reveals, I have feelings about that.

While those feelings aren’t nearly enough, I think it’s ultimately a good thing that I have feelings about that.